New guidelines aim to help people with dementia stay safe if they get lost

U of A researchers tap into experiences and ideas of people living with dementia to fill public information gap.

Lived experience

The strategies suggested in the guideline were based partly on interviews with people who have dementia and reflect what they’re already doing to cope, she noted.

“It comes from their own experiences; they’ve had to come up with some of these ideas themselves.”

Three in five people with dementia will become lost at some point, and research interviews revealed the issue is a growing concern. One Ontario police department reported six to eight calls about lost older adults per day. The risk of an incident ending in tragedy is high, Neubauer added.

“There’s a 50 per cent chance of being found deceased or injured if not found within 24 hours and if the weather is cold, it turns into a matter of minutes, not hours,” she said.

Being lost in a city poses the risk of being preyed on, while rural environments have hazards such as water and bush.

University of Alberta researchers have developed a new guideline to help people with dementia stay safe if they get lost, based partly on the experiences of those who are living with the condition.

“By including people with dementia, it tells them they can be active agents in their own care and they can keep themselves safe,” said lead author Noelannah Neubauer, an occupational therapy student in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine.

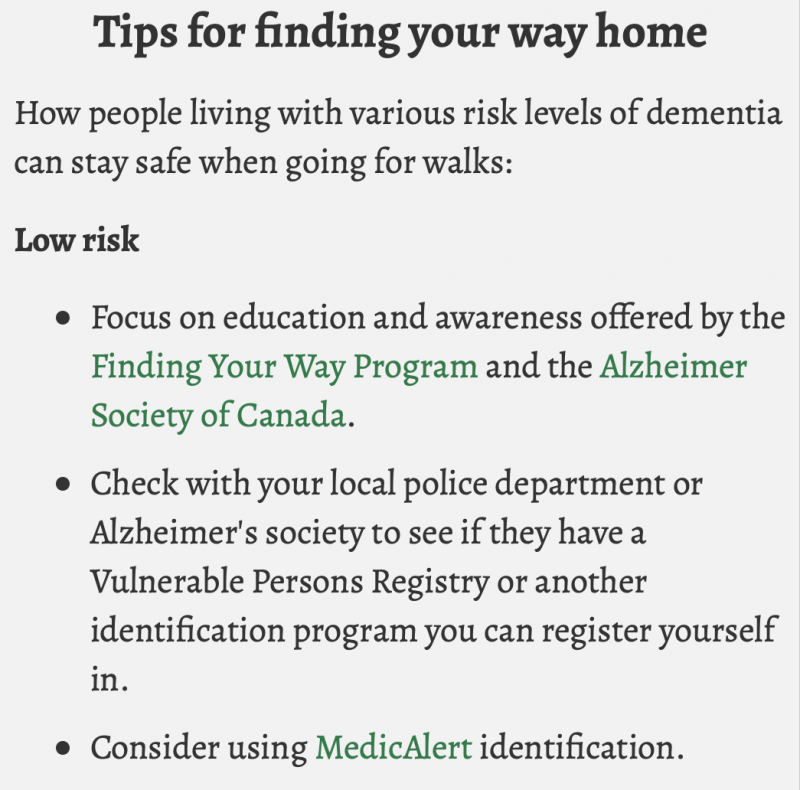

Tips for finding your way homeHow people living with various risk levels of dementia can stay safe when going for walks: Low risk

Medium risk

High risk

If you get lost

|

“The guideline opens up the idea that people with dementia can go for a walk as long as they have a strategy in place. It gives them some autonomy.”

The recommendations were developed to help fill in a big public information gap, she said.

“As researchers, we were getting a lot of questions from Alzheimer’s societies on how to keep people with dementia safe while they were living at home; they had no resources to refer them to.”

To find out what existed, Neubauer did a study of available literature that revealed a confusing tangle of more than 180 high- and low-tech solutions on how to keep people with dementia safe, ranging from home alarm systems to ID tags.

The researchers’ new guideline provides several measures, based on the risk levels of the people with dementia, for them to stay safe if they wander while living on their own—and many of them do live alone for various reasons, she noted.

“Many become divorced, lose friends, are estranged from families or don’t want to be a burden for their children, so don’t involve them.”

Some also fear being put into lockdown care prematurely.

“They feel they can maintain their sense of autonomy, which is hugely important for them,” said Neubauer.

Choosing an effective strategy

Neubauer and her co-authors also created a model as part of the study, that weighs factors that need to be considered when choosing an effective strategy to promote safe wandering.

“It gives people a customized approach. For instance, how comfortable is the person with using technology, what’s the surrounding geography of where they live, and what is their perceived risk of getting lost? This is the start of how we deal with someone that is at risk of getting lost.”

The guideline also reflects input and concerns from individuals looking after people with dementia.

“Many care partners don’t have peace of mind that they can find their loved one if they wander and get lost. But at the same time, they want them to be at home, not in a long-term care facility.

“The guideline gives them options for strategies they can try, and the importance of being proactive. For instance, as soon as there is a diagnosis of dementia, a couple can work together to identify what strategies the person with dementia is OK using. We’ve found that person wants to be part of those discussions.”

Long-term care facilities, including assisted living places that don’t have locked units, also benefit from a specific guideline aimed at educating everyone on staff, from nurses to janitorial and kitchen workers.

“Now they can use the guideline to understand the risks and what to look for in residents who may wander and get lost,” Neubauer noted.

Alzheimer’s societies, clinicians and some police forces have begun using the guideline, with interest expressed from U.S. home care and autism groups, Neubauer added.